In writing there is the power to put anything anywhere: the door you’ve placed in the text may be open; the door may be closed. Behind the door there is a garden; or behind the door is a slum, or a battle, or a chalk pit, or a king, dying; or nothing, or another wall with another door.

Vera Frenkel is an artist for whom language — particularly in terms of its malleability and unruliness — has served as an essential impetus, catalyst, and consequence for her storied career across nearly fifty extraordinary years of art-making. Moving between analogue and digital, documentary and fiction, departure and arrival, site and screen, Frenkel’s transdisciplinary approach is as much a process of migrating between her artworks’ evolving forms, contexts, and meanings as a reflection on migration itself. Since the 1970s, she has critically engaged with urgent socio-political issues of our time — including migration and exile, but also other conflicts inherent to communication, commodification, increasing bureaucratization, ongoing dispossession, and unrequited desire, to name but a few. Throughout, Frenkel has remained attentive to the linguistic underpinnings of her work, maintaining a keen sense of irony and wit in all that she writes, speaks, and represents. Referring to a work from 1974, the astonishingly prescient String Games: Improvisation for Inter-City Video, Dot Tuer observed in 1997 that “from her earliest experimentation with telepresence,” Frenkel has engaged the viewer in “an active process of piecing together meaning from fractured points of view.” Situating her works within indeterminate zones where the borders between oppositions begin to dissolve, Frenkel thus sustains a level of productive ambiguity that always holds a door open for others to enter and join in.

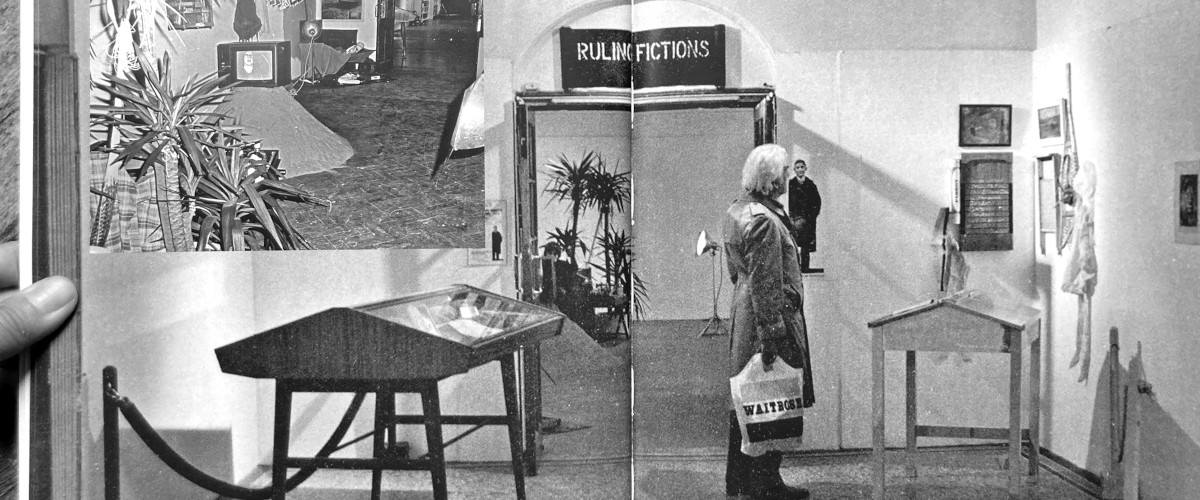

Ruling Fictions (The Small & Large Betrayals that Haunt Us Once Again) is a work that exemplifies many of these tensions and potentials. Originally created for a 1984 exhibition titled Vestiges of Empire at the Camden Arts Centre in London, Ruling Fictions took the form of an installation with video and tableaux, accompanied by a pamphlet with interlinked texts. The writing weaves together parallel narrative threads that encompass the artist’s inquiries and strategies for engaging, and often challenging, the institutions of Empire, art, archaeology, government, bureaucracy, and power interrelations thereof. As such, it is writing that catalyzes what Sigrid Schade has described as Frenkel’s interest in the “interplay between the construction of institutional archives and individual story-telling … illuminat[ing] blurred transitions between truth and fiction.”

Jonathan Shaughnessy concurs: “An essential premise for the artist’s use of works and words [is] that there is nothing necessarily foundational to language at all, or at the very least, nothing essential to words which can ensure that their propensity for Truth and Fiction cannot be undermined along every contextual step.” In an almost uncanny instance of reality mirroring fiction, 1984 was also the year that the Ontario Board of Censors was renamed the Ontario Film Review Board. In effect turning many artists into outlaws, this act affected Frenkel personally when she chose to move ahead with exhibiting The Business of Frightened Desires (Or the Making of a Pornographer) at an artist-run centre that had been shut down in the wake of a government raid.

Fast forward to 2019, the year in which I was researching artists for the site-responsive version of this exhibition at the Toronto Media Arts Centre (TMAC), an artist-run consortium that had itself become stuck in a legal battle with the city (albeit for reasons other than indecency). I had become interested in the possibility of installing a series of artist’s writings on walls within TMAC’s interstitial spaces, with the idea that this might also function as a kind of narrative thread for visitors exploring a show that was intended to manifest as a kind of fugitive presence within the troubled building. Frenkel and I had already been conversing on the increasing scarcity of space for art in downtown Toronto, and we discovered a shared interest in the Centre, as she had been working closely with one of the consortium members, Charles Street Video, on a new project. Encountering her writing within Ruling Fictions, I was struck by how it poignantly yet humorously captures the slippery nature of language in its power to cajole, caress, conceal, and coerce, often at the same time. In its direct address to the reader, its storybook quality, and spatially-oriented play, Frenkel’s text is equal parts exposition, proposition, and interrogation. Shifting in subjectivity and tonality, it manifests speech in a way that mirrors the strangeness and suddenness which with any conversation can turn in an unexpected direction.

The parallel and polyvocal form of the texts in the pamphlet made for a conceptual match with the idea of installing passages at key spatial turns in the building. In this way they would become a running counterpoint or commentary on the vicissitudes of mis/communication in parallel to the other more media-based or object-oriented installations within the exhibition. Focusing on 13 key passages, the texts broadly relate to, yet remain autonomous from, the other installations as both artwork and framing device. Unfolding as a fragmentary, nonlinear, and asynchronous echo from 1984, Ruling Fictions becomes all the more resonant in how it presages the accelerating crises of culture and communication we face today. Schade: “The present is permeated by history, and Frenkel’s works make these kinds of permeations visible.”

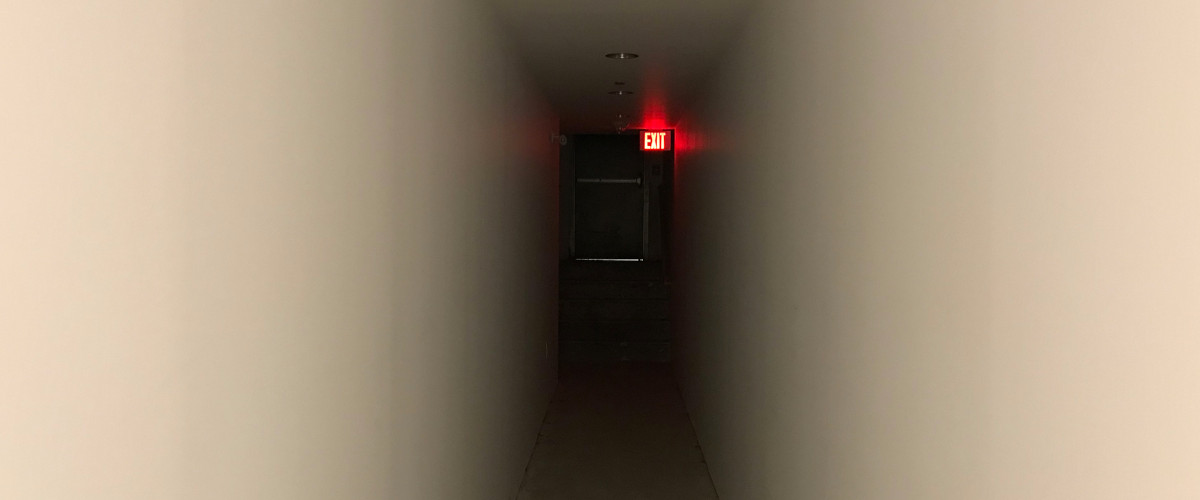

In 2000, Frenkel spoke on the role of art as testimony: “We’re here to talk about what happens when an event is experienced, remembered, and recorded in some way that allows it to enter history, accepting that this is a fragmented process, fraught with vested interests, contradictions, and denials.” Against such things as vested interests, contradictions, and denials — which condition all communications — how do our messages ever get through? Ultimately the physical form of this exhibition was never realized, cancelled in the wake of the pandemic and eventual eviction of the media arts consortium from the downtown building. Yet through an extended and complex process of communication, conditioned as much by chance and care as by conviction and crisis, the show is now realized in digital form, having undergone many more kinds of translation in the process. For example, while the artwork’s presentation may have lost a dimension in space, it has gained a dimension in time. Through setting the type in motion, Frenkel’s words now materialize letter by letter as a spectral form of writing on photos capturing the otherwise empty walls, mirrors, plinths, and halls of TMAC’s unfinished spaces before their eviction. The fragmentary passages thus map a place that no longer exists, except in these 17 images, teeming with absence and exits. In her 2013 essay, Work/Life Fragments, Frenkel observed, “Walls real and allegorical continue to rise and fall in constant redefinition of us-them, in-out, here-there….” Such dualities are key among the ruling fictions she interrogates, asking again and again: “Whose stories are these, after all? Whose are the fictions we live out, and why? Who are these people?” The question remains.

-----

- Special thanks to Vera Frenkel for providing the recordings that make this work accessible.

- Sound edit by Konrad Skreta.

- Image description by Jennifer Brethour and Kat Germain.

- The first and last photographs depict two spreads from Points of Departure: Words and Works (2016), published in conjunction with the exhibition Vera Frenkel: Ways of Telling (2014), curated by Jonathan Shaughnessy for MOCCA Toronto.

- Intervening photos document TMAC (2020/2021, since evicted from this Lisgar Street location).

- All photos by Shani K Parsons.